Introduction

There is significant disagreement between much of the literature with regards to the management of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis and to the efficacy of exercise intervention in establishing a meaningful long-term outcome. On the one hand many longitudinal studies are showing many physical therapies as not changing the eventual long-term prognosis of the condition. Yet there is also simultaneously a lot of literature on the efficacy of exercise on multiple measures showing categoric improvements on health and quality of life. Specific scoliosis intervention protocols Physiotherapeutic Scoliosis-Specific Exercises

(PSSE’s) have shown significant Cobb angle reduction, of up to a year follow up (1). Modalities that include PSSE re-education of postural alignment include methods such as “Dobomed, FITS, Lyon, Schroth, SEAS and side shift” (2).

The most common form of scoliosis is adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. A 50-year follow-up study on late-onset idiopathic scoliosis showed that 117 untreated patients and 62 age/sex matched volunteers found that patients with untreated scoliosis are, productive, high functioning and usually have little physical impairment other than back pain and cosmetic concerns. (3) Three major factors for progression include, magnitude of curve on presentation and growth potential as well as sex. Initial Cobb angle magnitude was the most important predictor of long-term curve progression. Sex, initial age and pubertal status were less important predictors. An initial Cobb angle of 25 degrees was an important threshold for predictive long-term progression (4). Growth potential is based on age and tanner stage, more precisely with radiographs for Risser grade, measuring bony fusion of iliac apophysis (5). Risk progression increases with higher Cobb and lower Risser Grade. A review by Reamy et. al (2001), concludes that physical therapy, chiropractic care, biofeedback and electric stimulation have not been shown to alter the natural history of scoliosis (6). In contrast bracing and spinal surgery at the required progression of the scoliosis and Cobb angle have shown efficacy as reported by Reamy et al. (2001). (6)

A review in 2005 indicates less need for radiographs, as it does not necessarily influence treatment protocol (7). An umbrella review of the literature in 2014 based on best evidence concludes that there were several systematic reviews that were scored as ‘moderate to low quality’ between 2002 and 2011. Indeed the 2012 US Preventative Service Task Force recommendation against screening was based on a low quality 2004 review (8). Plaszewski (2014) concludes that the suggestion for less screening is based on papers older that 10 years old and therefore outdated, and more importantly they did not review the methodological quality of these papers of which they included in their reviews. (8)

One such paper that claimed bracing and surgical intervention were the only route that made a difference, was cited by a 1988 study (9) as a locum of evidence for a study written in 2001 (Reference: 9) (6). More primary studies are therefore needed to methodologically assess the efficacy of screening as of 2014 (8).

Indeed, studies as early as 2003 have been criticising much of the literature against exercise intervention in the progression of scoliosis. Hawes (2003) concludes emphatically that there is not a single decisive study that mandates early exercise intervention of scoliosis is of no use (10). It is already known that given the known risks of curvature progression, possible chronic pain, psychological distress and possible reduced pulmonary function, early, and directed exercise prescription can facilitate long term health and productivity improvements in scoliosis patients. Hawes et al. also cites a need for more research on best practises after detailing historical problems with the approach of existing research (10).

Monticone et al. in 2014 conclude that rehabilitation programs including active self-corrections that focus on task orientated corrections and exercise as well as patient education have efficacy in reducing progression of spinal deformity and increasing health-related quality of life. It is however important to note that their observations were followed up for one year after which the intervention ended (1).

Kuru et al. in 2015 showed better results for Scroth method to a control group which was administered self-exercise at home. The Scroth group reported a lower Cobb angle, and the results of the other groups worsened. Patients were assessed pre-intervention at weeks 6, 12 and 24. (11)

Otman et. al in 2005, showed similar results with similar principle treatment protocols utilising the 3-Dimensional Scroth method for idiopathic scoliosis. Results recorded again at 6-weeks; 6-months; and 1-year showed a decrease in the Cob angle, however there was not a control group in this study.

The evidence for short term decreases in the cobb angle for up to a year post follow up certainly exists within the literature, and self-correcting programs through coaching and input by practitioners do show often superior results to other exercise programs with up to a year follow up. This includes the Scroth method which has plenty of evidence for its short-term validity are reported by the authors.

However, when many of these studies are further reviewed, in methodology and study design as well as referring to a systematic review by Mordecai et. al. (2012), reviewing the studies on decreased Cobb angles it is found that, they identified very few randomised control trials in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS). Concluding that most of the literature that show strong efficacy of intervention is weakly designed and do not have adequate control groups. Of the 9 studies examined only a single study had observer blinding. The review also noted that 5 out of the 10 studies all had conflicting interest and were all affiliated to centres that endorse exercise therapy for AIS. Recruitment of patients, age, sex respiratory function and radiographic parameters like Risser sign and other standard measurement practises for AIS. In Conclusion the “unbiased literature review has revealed poor quality evidence, for use of exercise therapy in treatment of AIS.” It is important that studies are publish using well-designed randomised controlled studies to properly assess, the role of exercise, as well as the different modalities used for these interventions.

With regards to another systematic review performed by Katharina et al. evidence published was cross referenced from and utilised from several authors from the same systematic review. This was done under the Schroth Spinal Deformities Rehabilitation Center in Germany. As can be seen, an independent review is needed for efficacy of these findings and the use of exercise therapy directed specifically for the treatment of AIS (11).

An interesting study comparing Cobb angles and other symmetrical measurements found improvement in both SEAS (scientific exercises approach to scoliosis) and core stabilisation, were similar in measurement. But the Core stabilisation group outperformed the SEAS group in the pain management scale based on the scoliosis research society 22-questionairre.

The most effective exercise methods for AIS indeed remains controversial (12). Long term results still seem to support orthopaedic long term studies that are dealing with a long term problem on the efficacy of the progression of AIS that points that scoliosis specific intervention is lacking a complete long term solution.

Discussion

A landmark study which presents a good proposition is the SOSORT 2018 winner – Which performed a high value randomised control trial in 2019 by Scheiber et al. They report that even if the Cobb angle did not improve beyond the accepted threshold of 5 degrees. Schroth treatment patients had an improvement in ‘perceived improvement in back status.’ They suggest that this study shows that it is worth considering alternatives to the Cobb angle which may be more relevant to patients. This is a very important study as it begins to think outside the box of the AIS trap – but rather suggest that we go back to outcome-based physiotherapy rather than trying to just fight back the Cobb angle (13).

At face value it shows efficacy in moving towards the biopsychosocial model that the profession of physiotherapy as a whole has consistently been moving in the UK as people start understanding that outcomes are of importance, but also the psychology and the patients’ needs must come first. We are not treating scoliosis but rather improving quality of life. And that includes self-efficacy – ability, activities of daily living as well as performance that is not only patient specific, but athlete specific. And adolescent needs to experiment, engage in different activities, interests, healthy living, sport, exercise. All these endeavours have unique and individualised demands on an adolescent.

Scoliosis has its own natural progression, but how can we keep the quality of life and what the patient sees most important at centre stage. Without rigorous evidence on the exercise effect on scoliosis and the different methodologies and programs that tailor to the condition rather than the wholistic picture of the individual physiotherapists can indeed miss the bigger picture. Programs such as Schroth although by their very nature are individualistic and catered in aligning the unique curves of each patient through stabilization and self-correction as well as postural control, in the end are only a small picture of what the patient, or rather, individual may want to achieve. There is also a limit indeed based on clinical best practise exercise science, that you can not hypertrophy and progress stabilisation indefinitely. So, although programs like PSSE’s (Dobomed, FITS, Lyon, Schroth, SEAS and side shift) definitely have efficacy and merit, you are not able to build strength and postural control in active sports, focusing only on these methods. An adolescent, desires to live a full and active life-style and as such, we must address all the drivers required for the safe, and efficient participation of the desired sport, physical activity and engagement.

It is also important to also understand the nature of various sports, and activities. A tennis player for example on service engages ground traction from the leg, through the hip and transfers this load through the spine. There is a co-activation of lower trunk muscles in order to stabilise the lumber spine. Under this amount of force, in such a short period, the player needs more than just local stabilisers however, or small corrective alignment of spine. A player in his sport, will be engaging also global stabilisers to exert force. And these strong rotational forces cannot be controlled or mediated through scoliosis specific exercises alone.

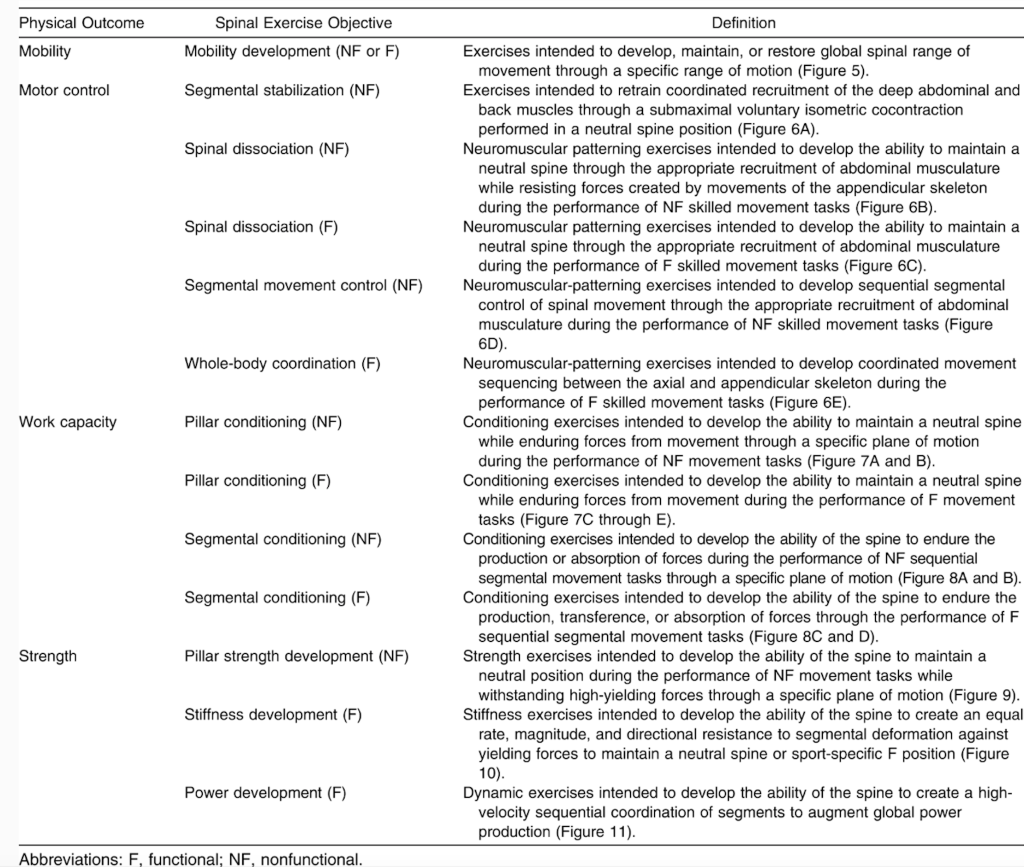

Indeed Mobility development, motor control, work capacity as well as strength must be developed for an athlete to not only compete safely in a sport but also in facilitating structural change and pillar strength if a therapist is even beginning of thinking of the possibility of improving postural control, and AIS in the long term. This however can not be thought of as AIS specific alone, but rather as holistic approach in order to create strength, and postural control in high torque motions that is required in any sport. This can be seen more completely in Figure. 1:

(Spencer, 2016 #279)

When addressing scoliosis with evidence-based practise, we need to have more considerations, as well as a holistic approach to what individual patient needs.

It’s important to familiarise ourselves with concepts such as “Give and Restriction” any long term plan for dealing with scoliosis as well as catering the adolescents needs with regards to efficient physical activity and healthy lifestyle.

“Give” is characterised as uncontrolled & excessive translation at a particular motion articular segment. It is an uncontrolled or excessive active ROM (Physiological) – Hypermobility/Instability. Characterised by a loss of motion or Restriction in the opposite direction. Site of pain is often termed the give, and the source the restriction. Treatment should focus on the restriction. This is where systems such as Schroth have shown to be of substantial use. Schroth, cannot really hypertrophy or change modular strength of intersegmental vertebrae, and this is likely why long-term results are scarce. It is a system that is built upon the ability for self-corrections in 3-dimesional space using breathing techniques, guided by a physiotherapist. There is however no evidence or reason to believe that this is a lifelong strategy of efficacy based on clinical reasoning, but rather a skill and tool, as well as stability exercise that allows the patient to be more cognisant of their posture, and learn how to make self-corrections, and become more independent in order to progress into periodisation and strength and conditioning, followed by sport specific considerations.

Possible identifiable postural dysfunctions that can be specifically and efficiently treated include:

- Tight Hamstrings (Forcing thoracic ‘give’)

- Tight Hip flexors (lordosis/kyphosis)

- Leg length discrepancy can often lead to scoliosis.

Leg length discrepancy should be routinely checked as there is an abundance of evidence that something as simple as correcting leg length discrepancy with a podiatrist, fitting adequate lift has shown that it can help in correction of AIS and cobb angles. It is called after all ‘idiopathic’ scoliosis because we do not know the exact reason for why it happens. If we can determine an observable leg discrepancy, this is something that could be addressed. Leg length discrepancy can change as an adolescent child grows, therefore will need constant monitoring and possible adjustments. Raczkowski et al. reports that leg length discrepancy equalisation results in elimination of scoliosis (Raczkowski, 2010 #296).

Isolation of muscle groups has a lot of research how to best achieve this and which exercises can adequately isolate different muscle groups. There is no evidence for those who claim can isolate and consistently strengthen or hypertrophy interspinous or a specific area along the spinous process.

We do however have evidence on how to isolate, strengthen and hypertrophy various important muscle groups for trunk control.

Conclusion and final Considerations:

Short term efficacy of treatments based on a long term progressive disease with a plan limited that is effectively pure marketing is not really evidence based practise. Scroth and other marketed treatment concept for scoliosis are left lacking. Entire systems claiming superior methods for specific conditions is a tool of profiteering, not of evidence based practise.

The concepts, of stabilisation, postural control, as well as progression into hypertrophy, isolation work, multi-plane strength training, functional progression and sport specific exercise, with adaptations towards functional thriving in activities of daily living – incentivising exercise and quality of life, through a biopsychosocial model, where function supersedes physical image is of the utmost importance. Intelligent individualised exercise prescription is evidence based. General “marketed” “scoliosis” “specific “systems” simply are not. There is no evidence that any of these systems having significant results in disease progression long term. Therefore adapting exercise and specifically designing functional adolescent child scoliosis, protocols to allow them to best be able to engage in their most fulfilled functional lives is more important. And to do this, we can borrow from a plethora of information of evidence based literature, and should never be enclosed to “marketed systems” of “efficacy”. Sport specific is the answer to better lives.. After all – the fastest man on Earth – Ussain Bolt, has scoliosis. In order to run fast – one must be balanced, and strong. The simple ability of strengthening the body through movement, in physiological movement is more important than focusing on intersegmental stability for a life-time, which is an impossible goal. Proper positioning of the spine can-not be achieved through simple static exercise and breathing. Sure it forms a part, of an evidence based intervention, but can-not be the main focus.

References:

1. Monticone M, Ambrosini E, Cazzaniga D, Rocca B, Ferrante S. Active self-correction and task-oriented exercises reduce spinal deformity and improve quality of life in subjects with mild adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Results of a randomised controlled trial. European Spine Journal. 2014;23(6):1204-14.

2. Negrini S, Bettany-Saltikov J, De Mauroy JC, Durmala J, Grivas TB, Knott P, et al. Letter to the Editor concerning: “Active self-correction and task-oriented exercises reduce spinal deformity and improve quality of life in subjects with mild adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Results of a randomised controlled trial” by Monticone M, Ambrosini E, Cazzaniga D, Rocca B, Ferrante S (2014). Eur Spine J; DOI:10.1007/s00586-014-3241-y. European Spine Journal. 2014;23(10):2218-20.

3. Horne JP, Flannery R, Usman S. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(3):193-8.

4. Tan KJ, Moe MM, Vaithinathan R, Wong HK. Curve progression in idiopathic scoliosis: follow-up study to skeletal maturity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(7):697-700.

5. Greiner KA. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: radiologic decision-making. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65(9):1817-22.

6. Reamy BV, Slakey JB. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: review and current concepts. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(1):111-6.

7. Bunnell WP. Selective screening for scoliosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005(434):40-5.

8. Płaszewski M, Bettany-Saltikov J. Are current scoliosis school screening recommendations evidence-based and up to date? A best evidence synthesis umbrella review. European Spine Journal. 2014;23(12):2572-85.

9. Lonstein JE. Natural history and school screening for scoliosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1988;19(2):227-37.

10. Hawes MC. The use of exercises in the treatment of scoliosis: an evidence-based critical review of the literature. Pediatric Rehabilitation. 2003;6(3-4):171-82.

11. Mordecai SC, Dabke HV. Efficacy of exercise therapy for the treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a review of the literature. European Spine Journal. 2012;21(3):382-9.

12. Yagci G, Yakut Y. Core stabilization exercises versus scoliosis-specific exercises in moderate idiopathic scoliosis treatment. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2019;43(3):301-8.

13. Schreiber S, Parent EC, Hill DL, Hedden DM, Moreau MJ, Southon SC. Patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis perceive positive improvements regardless of change in the Cobb angle – Results from a randomized controlled trial comparing a 6-month Schroth intervention added to standard care and standard care alone. SOSORT 2018 Award winner. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2019;20(1):319.

Author:

Constantinos Hadjichristofis – Bcom Human Resource Managment (Wits) PT (ACSM) BSc (Hons) Physiotherapy (Herts) MSc – Sports Medicine, Exercie and Health (UCL).